It was the tension between Janette Beckman’s shyness and her curiosity about people that helped spark a career photographing subcultures. “I realised that having a camera gave you licence to go up to strangers and say, ‘Hi, I’d like to take a picture of you,’” she says. This epiphany jump-started a 45-year adventure in street photography, documenting the punk and two-tone youths of 70s Britain, the birth of hip-hop in New York, Latino gang members in Los Angeles, bikers in Harlem, rodeos, rockabilly conventions and demonstrations from Occupy Wall Street to Black Lives Matter.

As we talk on a video call, 62-year-old Beckman gives me a tour of her home studio in New York, just off the Bowery where the famous punk venue CBGB used to be. There’s a Salt-N-Pepa snowboard, a Keith Haring painting and gold discs from hip-hop stars Dana Dane and EPMD. On one strip of wall hang a selection of images from Occupy Wall Street in 2011, “for a book,” she says. And on another are pinned a vast selection of her images, for her monograph Rebels: From Punk to Dior.

There are so many familiar shots. Salt-N-Pepa in 1987, sassy in leather and bling; Salt writes in the book that Beckman captured “the essence of who we were at that moment, young vibrant women on a mission to conquer this male-dominated genre called hip-hop”. The Beastie Boys pose in a comic huddle in 1985; Ad Rock writes: “Janette’s like a mind-reader … Her work is one OH-SHIT! after the next.” LL Cool J rocks a Kangol hat and carries a boombox on his shoulder. De La Soul gather on home turf in Long Island in 1990 – as DJ Maseo has it: “Janette caught us being us.”

Beckman has a knack of prompting her subjects to bare their souls like it’s an act of defiance. “You form this intense relationship very quickly with your subjects, or that’s what I try to do,” she says. “I’m the antithesis of somebody like Annie Leibovitz, who would have 20 assistants and take the subject up to the top of the mountain or have a helicopter flying over.” Beckman likes to keep it simple. “Rather than go in with a preconception about who the person is, I don’t want to know too much because I want them to tell me who they are.” She captures the attitude, she thinks, by catching “a moment between ‘posing’, when the subject has a chance to breathe and be themselves”.

Beckman’s fascination with portraiture started young. “Growing up in London,” she says, “I spent a lot of time in the National Portrait Gallery. And I would stare at people on the bus to school trying to imagine what their lives were like.”

She started her art foundation course at Central St Martins, aspiring to be the next Egon Schiele or David Hockney. “I was living in this semi-squat in Streatham where we were all drawing each other, and all we cared about was art and music.” But she didn’t think she was good enough, and signed up for what was then the London College of Printing (now London College of Communication), “to do photography, as another way of doing portraits”.

She soon became obsessed with the early 20th-century documentary photographer August Sander. “He was documenting people on the street,” she says. “They’re just really simple portraits.” One of Beckman’s most enduring images is of the British Nigerian twins Chet and Joe Okonkwo – who used to dance on stage with Madness and became locally famous in London for their sharp looks and lively conversation. Taken in 1979, it was featured in the first issue of the Face magazine. “It’s my homage to [Sander],” she says, “because it’s a really simple portrait, but it shows who these people are.”

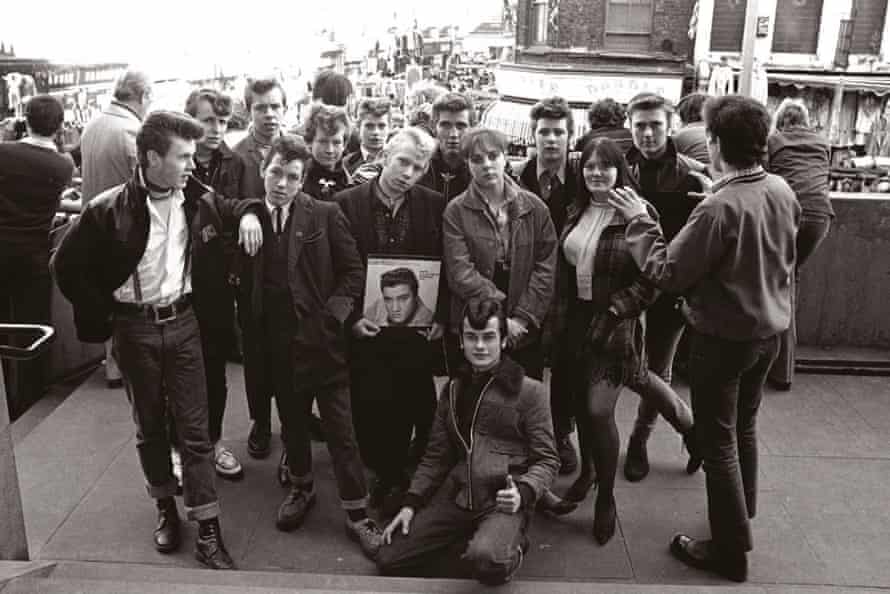

The Face, together with rival style magazine i-D, helped pioneer street style photography, and the editors gave Beckman free rein. “They would send me to an illegal boxing club in south London, or maybe some rock festival by Loch Lomond, where I could go and shoot the fans as well as the bands and they would do spreads of all the fans. That gave me licence to document all these youth cultures.”

In 1982, Beckman relocated to New York. “Punk was on the wane by then, and there was that Thatcher-era, ‘everything’s shit in England’ attitude.” And she’d discovered hip-hop. “There was something about the energy which was so different from London. It was exciting.”

The first hip-hop tour had come to London a few months before she moved. The stage was flooded with DJs, rappers, graffiti artists, breakdancers and double dutch girls, who did elaborate skipping routines with two ropes. “It was a renaissance moment for me,” she says. “Unfortunately the writer didn’t think so. He wrote something like, ‘This rapping is a fad, just like skateboarding’ – it was hilarious.” Little did he know that he was reviewing some of the godfathers and godmothers of rap; Fab 5 Freddy, Afrika Bambaataa, graffiti writers Futura and Dondi, and DJ Grandmixer DST.

In the early 80s, New York was recovering from near bankruptcy and undergoing an incredible cultural renaissance, from hip-hop in the Bronx to the art scene downtown. Beckman lived in Tribeca, which was then “a deserted warehouse neighbourhood”. The famous Mudd Club, where Fab 5 Freddy taught Debbie Harry how to rap, was around the corner. “It was really great,” she says. “And it was dangerous.” Naive and brazen, she would wander around the Bronx or travel to America’s west coast to loiter in LA ganglands, searching for interesting characters.

Hearing about these adventures reminds me of my own US road trips, where my female friend and I often found ourselves in strange backwaters we had been warned about, only to be greeted with kindness and curiosity. Beckman nods in recognition. “I think I got a lot of respect, because I’m British, I’m a smallish woman with a camera, not intimidating. So people trusted me. You are really a stranger on somebody else’s turf and they somehow respect you for being there and not being scared.”

In recent years, Beckman has been invited to train her lens on high fashion. In 2019 she shot Dior’s autumn collection in London’s Kentish Town, against the walls where she’d once immortalised young punks. Dior’s creative director, Maria Grazia Chiuri, had commissioned her in 2016 to document the making of a collection at her Paris atelier. “I went to see the tailors, and to watch people sewing on sequins, models smoking in the backyard and being dressed, and the rows of shoes,” Beckman recalls. I ask whether shooting the fashion world felt less authentic than street photography, but she describes the job as “gritty, down-and-dirty, rather than superstarry. These worlds seem so glamorous, but behind that are working people trying to make the glamour.”

Many of Beckman’s old New York hangouts have long since been gentrified and taken on a homogenised hipster veneer. When she moved to her current address, in 1996, it was “industrial, with parking lots and a lumber yard, a plumbing supply store”. Now it’s “really chi-chi”. Meanwhile, the internet means that no sooner is a new youth trend identified than a big brand is mining it for viral marketing content.

But Beckman doesn’t believe any of this marks the death of subcultures. She mentions the black punk scene in Brooklyn, as documented by her photographer friend Destiny Mata, and says “there are always going to be subcultures. There are always going to be people popping up with new ideas, whatever age they are, and wherever they’re from.” She concedes, though, that the internet can pluck emerging cultures from their communities too soon, so they “don’t have time to marinate”.

But Beckman continues to follow her nose and often that takes her away from coastal cities – to the Black Bikers Club in Omaha, say, or speedway races in Indiana. In 2017, after Trump’s election, Beckman began a three-year project called I Vote Because, for which she travelled through America’s swing states taking portraits and encouraging people to register to vote. “You got incredible stories from people in five minutes,” she says. “It was a dream job.”

That’s not to say there isn’t plenty of underground activity in New York, from illegal girl fights in Brooklyn to a group of dirt bike riders in Harlem (also illegal) called the Go Hard Boys, who made an exception to their no-photography rule for Beckman. The bikes – as well as an affiliated dance school – are a diversion from drugs and other bad influences.

She recalls her first time photographing them in 2008: “I was riding in the back of a flatbed truck down the Bruckner Expressway with these people doing wheelies. It was dangerous, kind of crazy when I think about it. But I was just so happy.”

-

Rebels, From Punk to Dior by Jeanette Beckman is published by Drago at €60

-

A caption on this piece was corrected on 1 December; the Specials were photographed in Blackpool, not Southend.